An Introduction to Stock Markets

Introduced with minimal background

In a time before written history, some unknown person thought it would be a good idea to invent the concept of currency. It’s something we agree on to be valuable in increments, which lends itself to usage for trade or whatnot. People kept doing this, and after a while they had already added an alarming amount of complexity, leading to the need for accounting, which some modern historians claim led to writing. Things got out of hand from there.

At its most simple, the stock market is somewhere you can request and perform transactions to buy or sell stocks. Stock is, legally speaking, a slice of ownership of a corporation. At some point, there was an expectation that the company would take excess profits that were not being split off to grow and maintain the business and divide them amongst the shareholders in what’s called dividends. However, that’s not particularly the expectation anymore. The dollar value of a stock is supposedly tethered to the value of the corporation’s assets (things they own that can produce value, whether machines or patents) combined in an unknowable and imperfect manner with the expectation of what the company’s total assets could be in the future, and thus their greater profits, which may lead to higher dividends1, and thus making the held shares worthwhile.

For instance, Apple and Microsoft pay dividends, but Amazon and Tesla don’t. In a rational market, why squabble at hundreds of dollars a share over these stocks when they don’t plan to pay dividends soon — wouldn’t it be better to place your money somewhere where they have promised or already do so? The answer is yes, it would be, but to not think about this and ignore it. The stock is worth that amount largely because someone agreed to pay that much for it. It’s for the best if you don’t think about this, and instead view a stock as an abstract, tradeable blob that can be assigned worth.

That sucked. As I was saying, the stock market is a venue, formerly physical but now largely abstract, where formerly people but now largely computers convene to make offers or take offers to buy or sell some stock. Breaking that down, they can either make an offer to buy or sell an arbitrary amount of stock, or they can agree to someone else’s offer, and sell or buy some amount of stock. These offers and their taking are henceforth referred to as Orders. Taking part in one of these orders on either side is called Executing or Filling the order. Let us now discuss the details of this exchange.

Alice seeks to part with her 100 shares of ExCorp stock2. She goes up to Market Mallory, the one who handles the execution of trades, and instructs her to sell these shares using what is called a Market Order. The market order will attempt to give the best price for its transaction. It executes immediately in almost all cases since it will immediately take the best order that is hanging around out there, in her case, the order that is willing to pay the most to buy this stock. Market Mallory looks over at her Order Book, a collection of all orders that have not yet been filled, and observes that the highest buyer price (known as the Bid Price) is $100.003. To her indifference, but Alice’s dismay, the order is only to buy 80 shares, and as such will be completely filled by Alice’s market order — but Alice’s market order is not yet complete, with 20 shares awaiting sale. The filled order, now completed to satisfaction, is removed from the order book. Moving down to the next highest price, 30 shares at $99.50, Mallory fills Alice’s market order. This leaves her with $9,990 (versus a potential $10,000) but only partially fills the order at $99.50, with the other 10 remaining for someone else to take.

Over in New York, Bob gets a note from Market Mallory that there was a partial fill on one of his orders. You see, just a few minutes ago, he placed a Limit Order to buy 30 shares of ExCorp at $99.50, which will stay in the order book until entirely filled, or he tells them to cancel it. The order will only be filled by people looking to sell at $99.50 or lower, which Alice’s market order was willing to do. As he waits for the other 10 shares to fill, he looks over at the order book for ExCorp and notes that the lowest price someone is willing to sell their stock for, called the Ask Price, is $100.75. Thus, the ask price is the price Bob will buy at if he wants to buy more ExCorp. That’s a lot, so to be clear, the bid price is the best price a buyer is offering, and if you want to sell, you take their deal — while the ask price is the best price a seller is offering, and if you want to buy, you take their deal. The difference between the bid and ask price is called the Bid-Ask Spread. When one wants to make a market order, one must implicitly eat the price of the bid-ask spread to receive immediate order execution, meaning that were you to immediately close the position (sell the same amount if you bought or vice versa4), you would lose however much money the bid-ask spread was. For example, if you bought at $99.50 and the bid-ask spread is $100.75-$99.50=$1.50, were you to immediately sell, you then have ($100.75)+$99.50=($1.50). Parenthesis with dollar values, particularly in accounting and finance, notate negative values.

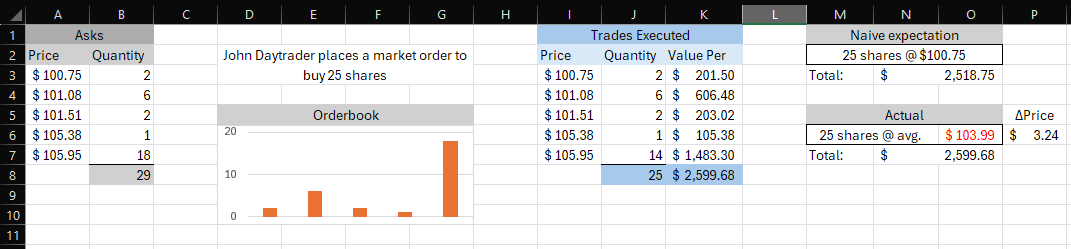

This touches on an important symmetry between market orders and limit orders. Market orders guarantee execution time but do not guarantee the price, while limit orders guarantee the price but not the execution time. In their conventional usage, the two orders take complimentary roles as what is called Liquidity Taker and Liquidity Maker orders, usually just called Maker or Taker, for limit and market orders respectively. Liquidity is the ease with which one can efficiently transact on the market — that is, without significant changes in asset price or incomplete order fill. It follows that if someone submits a limit order, they add liquidity by adding further Depth to the order book, or orders that are available to be filled. Someone making a market order will partly or wholly take some of these offers from the order book, which would constitute taking liquidity. As a counterexample, were someone to make a market order in a Thin Order Book, that is, one where the best few quotes are of low quantity, they may experience a considerable change in the actual price of their order compared to what they thought, called Slippage. This is a lot, so here’s an illustration.

In particular, note ΔPrice, which represents the slippage of the naive price versus the average slippage-adjusted price. There is, however, a market participant of great value that can help John to not faceplant; the Market Maker.

The market maker is a fascinating participant in the market, one who makes money rain or shine while also increasing liquidity. Their role is to constantly hold the best quotes for the bid and ask sides of the book, facilitating the purchase and sale of stock. Interestingly enough, in a theoretical respect, the market maker is neutral to the overall trends of the market and is instead happier when the Volume, or the amount of shares traded, is high. This often occurs when Volatility is high, which is a measure of how much a price varies with time, with volume increasing as participants rush to close or open5 positions when the price is changing quickly. To maintain this neutral outlook on the trends of the underlying asset being market-made, the market maker would prefer to keep minimal stock on hand — the minimization of Inventory Risk. If things go downhill very quickly6, such as a company declaring bankruptcy or other drastic moves, were the market maker to have an open position on the company, they may be unable to find buyers to offload this stock and are thus at the mercy of the changing price. The compensation for taking this risk is how the bid-ask spread is traditionally determined, which tends to imply that the bid-ask spread, and thus the market maker’s compensation, is proportional to the volatility.

The market maker cares a lot about the fine details of the order book, as their systems benefit considerably from predictable order book behavior, enhancing their ability to re-adjust their position, thus reducing potential risk exposure and beating competition to the Order Queue. When you place a limit order on the book at a price that already has an existing order, in many exchanges7 the orders are executed on a first-come-first-served basis, or FIFO. That is, if we have two quotes for $100 on the same side of the order book, the order that arrives at the exchange first will be the first in the queue and will be executed first. Were this first arriving order to be fully filled, but the order that filled it has not yet been completely filled itself, it will move to the next order in the queue. If it exhausts the entire stack, then it will slip to the next quote. Numerous factors, from infrastructure to the design of the software, play a role in making the time from decision to the order being on the books as small as possible.

Now that the major features of the market are elaborated, we can dig down on the pedantic details. The elephant in the room is that despite having phrased everything in the sense of shares of stock, corporate stock is not the only thing transacted on our modern financial markets. From bundles of stock called ETFs to types of Derivatives like Futures or Options contracts that have their price based on the value of an “underlying” asset, a good number of things are run in the same or similar formats. All exchanges, including popular ones like the NYSE or NASDAQ, have different rules and permit different assets to be traded on their platforms, differing in big and small ways. The details are monotonous and painful, but in general, a Broker-Dealer performs the trade for us, nicely abstracting away the complexity at the very least for stocks or options.

Second, not every exchange of stock occurs on an open market — in fact, 40% do not. Dark Pools, formally known as a form of Alternative Trading System (ATS), are private exchanges that do not expose trades to the public market. This mechanism is useful for making large trades without impacting the wider market — as the sight of unloading tens or hundreds of thousands of shares onto the open market does not particularly inspire confidence. Once this order is filled, though, it becomes public knowledge and then will impact the price.

In addition to this, there are a good number of orders and subtypes of orders that have not been discussed at length here. Things like the Immediate Or Cancel (IOC) more finely dictate the timespan of the order, in this case, IOC requires at least some portion of the order to be filled immediately, before immediately canceling it. A subtype called the Fill Or Kill (FOK) exists, which requires full fill immediately. This trait, in turn, inherits from the All Or Nothing (AON) order, which indicates that no partial fills shall occur on this order. The default type of order, the Day Order is canceled at Market Close if it isn’t executed or canceled beforehand, which occurs at 4:00 PM EST on most major U.S. exchanges. On the other hand, the Good-Til-Cancelled (GTC) order is more or less what it says, and persists forever, or up to a limit set by the broker-dealer, usually at 90 days. In addition to these, there are many types of orders dependent upon price to execute, for example, Stop Loss or Sell Stop orders that behave like a sell market order when a stock falls past a certain price, and their corollary the Buy Stop which buys instead when a stock rises past a set price.

Discussion of these mechanics could go on for many books worth of information, but I have tried to choose the information most pertinent to deeply understanding the trade of securities on our modern markets — a task that is not trivial — but have had to omit details or oversimplify here and there in ways that vary in impact. There are numerous resources available that discuss financial markets as a whole, both at this high-level view and regarding the details of the markets themselves and how to interact with them. The complexity contained within the financial markets is immense, both from our designs, and the behavior emerging from the interplay of these designs with innumerable participants. People dedicate their careers to understanding the complexity of these markets, but none will ever get close to fully understanding them.

They could also get acquired, or give shareholders the option to sell their stock to the company.

You see, Alice, an advanced computer program written by hordes of well-compensated mathematicians, has just gotten wind through her 100Gbps microwave internet link that ExCorp X’d a Y, and is now facing Z. Sentiment analysis has determined this is unfavorable, and, as such, has sent the order to sell all of it, doing all of this in the time before John Daytrader’s White Claw makes the trek from the tip of the can to his tongue. You are gambling, they are playing.

As for the price you see on the news or summaries of stock prices, that is usually the last transacted price of the stock, that is, the price at which the stock was last sold or bought.

You can also have a position where you have to buy to close the position, which is called a Short position. This would mean you technically have a negative number of shares since you have sold a share lent to you by someone.

The opposite of closing a position, opening a position is the act of making a bet by buying or shorting a stock.

Or uphill, for that matter, were the market maker to be holding a short position. See footnote 4.

Notably, the NYSE does not follow the FIFO model, instead opting for Parity/Priority, which aims to not reward speed.